What Is A 1031 Exchange?

Let’s start with the basics: what is a 1031 exchange?

A 1031 exchange is named after the Section of the Internal Revenue Code that defines its many rules and regulations (much like a 401(k) or 403(b) account). It helps real estate investors achieve one of the holy grails of investing: the deferral of capital gains taxes when selling an investment property, simply by reinvesting the proceeds of the sale into a subsequent, and similar, investment property.

Done correctly, the second real estate purchase assumes the cost basis of the original purchase, and capital gains taxes are deferred until the ultimate sale of the newly acquired real property. Of course, when it’s time to sell the second property, another 1031 exchange can be executed, so the business of paying taxes on your sales can, in theory, be deferred indefinitely. It’s not unheard of for savvy real estate investors to defer capital gains taxes for decades by stringing together a number of 1031 exchanges, year after year. Many professional real estate investors even use 1031 exchanges as a central component in their estate planning.

Sound simple?

Not so fast.

Potential Pitfalls of a 1031 Exchange

While the potential benefits of a 1031 exchange are compelling enough to encourage any real estate investor to consider them, there are many potential pitfalls to a 1031 exchange.

These can involve:

- the timing of the sale and purchase of the real property in question

- the nature of the property being sold as well as the one being bought to replace it

- the eligibility (and ineligibility) of certain kinds of investment properties

- how the proceeds of each transaction are handled

- how to address discrepancies in value (since one property is rarely exchanged for another with its exact value)

- the process of identifying suitable properties for purchase after deciding to sell the original piece of investment real estate

These are only some of the areas in which an unaware real estate investor may run afoul of Section 1031, and any one of these critical errors could be enough to render the exchange ineligible for the valuable benefits offered by the IRS, even if all of the other rules are followed to the letter.

Know and Understand The Rules of a 1031 Exchange

What is true of most real estate investments is doubly true of the 1031 exchange: it is critical to know and understand the rules surrounding these transactions, and essential for even the most experienced real estate investors to enlist professional help in following them all. In the field of 1031 exchanges, such pros are known as qualified intermediaries, exchange facilitators, or exchange accommodation titleholders, and their importance to a successful, IRS-compliant transaction cannot be overstated.

Reasons Why An Investor May Consider A 1031 Exchange

There are many different reasons why an investor may consider using a 1031 exchange, such as:

- They may be seeking to consolidate several properties into one (or, conversely, they may be looking to sell one investment property and replace it with three or more alternatives).

- They are hoping to upgrade their investment property or to invest in one with potentially greater investment returns.

- They might even have a goal of transforming a second home, or a vacation home, into an investment property via a carefully constructed 1031 exchange.

The factor common to all of these diverse factors is: the deferral of capital gains taxes.

That’s why I’ll be addressing every critical aspect of 1031 exchanges in this Guide to A 1031 Exchange, not only to encourage investors to consider these exchanges carefully in lieu of paying a potentially exorbitant and possibly avoidable capital gains tax, but to educate investors about the process so that they are able to take full advantage of something that the IRS rarely offers (and never offers without strings attached): a valuable tax break!

History of 1031 Exchange

Since we know that 1031 exchanges offer a way to potentially defer capital gains indefinitely, we know that the root of the exchanges lies in the Internal Revenue Code, or the IRC, specifically, section 1031 of the Code. What may surprise many investors is that the exchanges are almost as old as the Code itself.

The first version of the IRC was adopted by Congress in 1918 as part of the Revenue Act of 1918, but did not allow for any tax deferral mechanism involving like-kind exchanges. Three years later, however, the Revenue Act of 1921 enabled investors to defer taxes on exchanges of securities and non-like-kind properties, enumerating these rights in Section 202(c) of the Code. Congress reversed itself quickly, eliminating the non-like-kind property provisions in the Revenue Act of 1924, and subsequently reaffirming deferral on like-kind exchanges in the Revenue Act of 1928, while also moving the relevant language to Section 112(b)(1) of the IRC.

It wasn’t until 1935 that like-kind exchanges began to more closely resemble the format we recognize today, as the Board of Tax Appeals approved like-kind exchanges that not only deferred capital gains taxes for the exchanges of similar assets, but introduced the Qualified Intermediary as an essential part of the transaction. Importantly, the “cash in lieu of” clause, which allowed for the proceeds of the sale of one property to be exchanged for a like-kind property (instead of requiring the exchange of the properties themselves) was also upheld.

Finally, the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 achieved its goal of consolidating the IRC provisions from 1939-1953, revising and renumbering the existing Code sections for overall ease of operations. In so doing, Section 112(b)(1) was reborn as Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code, laying the groundwork for the modern structure and functions of the exchanges that bear its name.

Subsequent evolutions of 1031 exchanges broadened their appeal and deepened their value to tax-averse investors seeking to capitalize on appreciated assets while minimizing the bite of taxes.

We’ve used the terms “1031 exchange” and “like-kind exchange” interchangeably; they are also frequently referred to as “Starker exchanges,” or “Starker trusts.” The name stems from a 1979 court case, Starker v. United States, in which the Starker family contested the IRS decision that their sale of timberland to a corporation, in exchange for a contractual promise to acquire and transfer title to properties identified by the Starkers within five years, did not qualify for a deferral of their income tax liabilities. The eventual decisions from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals set the precedent for what we now know as non-simultaneous, delayed like-kind exchanges. The Starker decisions also forced Congress to establish regulations governing non-simultaneous, delayed like-kind exchanges. As a result, the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 introduced the 45-calendar-day identification deadline, as well as the 180-calendar-day exchange period. We’ll be discussing these important timelines in greater detail in future sections of this guide.

Not long after, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 changed the treatment of capital gains, resulting in all capital gains being taxed as ordinary income. Combined with a handful of accounting changes that accompanied the capital gains tax treatment, the 1031 exchange emerged as one of the few, and best remaining, income tax benefits available to investors, especially those with real property investments.

In 1990, the Department of the Treasury proposed rules which codified and finalized the 45- and 180-day timelines first established in 1984. They also provided guidance on constructive receipt issues, clarifying the definition of “simultaneous” and “improvement” exchanges under Section 1031, and further defining the eligibility of Qualified Intermediaries under Section 1031. These proposed rules were issued as final regulations in June of 1991, and remain an integral basis of 1031 exchanges today.

While other minor tweaks helped to form the current version of the 1031 exchange, the only other major development was the IRS’ decision to issue Revenue Ruling 2004-86, which paved the way for investors to take fractional ownership of interests in real property through Delaware Statutory Trusts, or DSTs. By ruling that DSTs qualified as a suitable replacement property solution for investors seeking to execute a 1031 exchange, it provided investors with an alternative to seeking out one or more real properties on their own, in theory facilitating increased participation in 1031 exchanges for investors.

As the foregoing history demonstrates, 1031 exchanges have existed for decades, and are likely to continue in some form for generations to come. Their evolution also demonstrates the ongoing need for investors to remain vigilant on any and all legislative attempts to strengthen this important tax benefit – or to weaken it. Multiple attempts have been made over the years to alter or even eliminate Section 1031 benefits, and while none has succeeded thus far, future attempts are virtually certain.

Our goal here, and in our Master The 1031 Exchange Masterclass, is not only to educate you on the current state of 1031 exchanges but also to keep you informed on any future changes that may take place.

Who is Eligible for A 1031 Exchange?

The appeal of 1031 exchanges is obvious to savvy investors: the ability to defer, or even (by virtue of savvy estate planning) eliminate capital gains taxes, is a powerful financial incentive to consider an exchange. So let’s delve into the eligibility requirements for a 1031 exchange.

Requirement #1: The first requirement seems simple enough: to be eligible for a 1031 exchange, you must be a real estate investor, in possession of an appreciated piece of real property.

Let’s start with the simplest word: you.

For the purposes of a 1031 exchange, “you” can certainly be an individual investor. But you can also be a partnership (general or limited), a corporation (“C” or “S”), a trust, a limited liability company (LLC), or virtually any other tax-paying entity. In short, if you can own investment real estate and pay taxes on it, you can structure a 1031 exchange when selling the property in question.

Requirement #2: Both properties in the exchange—the one being sold, and the one being acquired—need to be investment real estate.

That’s another important IRS requirement: we’re talking about investment real estate here. So while individual investors are eligible, they can’t structure a 1031 exchange based on a desire to sell their primary residence or even a vacation home, and shield themselves from capital gains by investing the proceeds into a piece of investment property. Both properties in the exchange—the one being sold, and the one being acquired—need to be investment real estate. Section 1031 of the code makes it clear that properties held for use in a trade or business also qualify as investment properties for the purposes of an exchange.

A caveat: some folks have found a workaround in the case of second homes, or vacation homes, by transforming them into investment properties by renting them out for a period of time before selling them. A 2007 Tax Court case determined that properties held for personal use, even with the hope or expectation of capital gains, did not qualify as investments if the investor used them exclusively for their own use, or for the use of family or friends. A subsequent 2008 revenue procedure clarified that real properties qualified for 1031 exchanges if they were held by the investor for at least 24 months prior to (or subsequent to) the exchange, and for each of the two 12-month periods, they were rented at fair market value for at least 14 days, while restricting personal use to 14 days OR 10% of the number of days it was rented at fair market value, whichever was greater.

Requirement #3: The property being sold, or relinquished, must be an appreciated piece of real estate.

Finally, since the goal of a 1031 exchange is the deferral of capital gains tax by the investor, it stands to reason that the property being sold, or relinquished, must be an appreciated piece of real estate. As such, under ordinary circumstances, its sale would generally trigger a capital gains tax. If you’re somehow holding a piece of investment real estate whose sale would post a loss instead of a gain, there’s no need to consider a 1031 exchange, or any other investment technique designed at minimizing taxes. That’s the sole upside of a bad real estate investment: the tax man has no interest in your transaction!

Requirement #4: You must reinvest the proceeds into a like-kind exchange.

Assuming your real estate investment follows the pattern of the lion’s share of such transactions, and is subject to capital gains tax upon sale, the final requirement is your willingness as an investor to reinvest the proceeds into a like-kind exchange. In other words, you must sell your piece of investment real estate and subsequently buy another, usually more valuable, piece of real property that will also be an investment property.

Requirement #5: You must avoid a common pitfall to keep the tax man away.

If not properly structured, only a portion of a 1031 exchange might qualify for the deferral or elimination of capital gains taxes. Sometimes the replacement property is valued at a lower price than the relinquished property; the resulting difference between the two prices, known as boot, would present the investor with a tax bill based on the amount of the difference. (Learn more about Boot in Lesson 1 of Master the 1031 Exchange.)

Another common example of boot occurs when there is an unpaid mortgage on the relinquished property, but not on the replacement property. IRS regulations consider any debt the investor is relieved of as a result of the transaction to be money received. So if the investor sells the relinquished property and pays off mortgage debt with sale proceeds, the IRS would likely see this as a taxable gain to the investor and tax it accordingly. The easiest way to avoid mortgage boot is to encumber the replacement property with the same amount of debt as the relinquished property had on it.

There are other ways in which 1031 exchanges may result in boot, and several options to mitigate the situation, all of which merit a full discussion in a future chapter. For now, it’s enough to take note that actually paying the tax bill in question is a last resort, and one that can usually be avoided.

Requirement #6: You must follow strict timelines.

Ultimately, if you are ready, willing, and able to follow the timelines and other requirements proscribed by Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code, both your sale and your subsequent purchase will qualify for the preferential tax treatment of your resulting capital gains. We’ll examine these timelines and requirements in great detail in subsequent chapters of this guide, as we do in our 1031 Exchange Masterclass.

Understanding Delayed 1031 Exchanges

With 1031 exchanges offering such compelling tax advantages, the kinds of exchanges that are possible have evolved over the years. Decades ago, when the Internal Revenue Code first authorized the exchanges, there was only one kind, and it was extremely limiting. Now known as the simultaneous exchange, it required both the sale of the appreciated property and the acquisition of the subsequent property to take place at the same time.

Eventually, the code was modified to permit exchanges that allowed for some time to elapse between the sale of one property and the acquisition of the replacement property. These delayed 1031 exchanges are now the most frequent kind of exchange, and while they are relatively straightforward to structure and execute, they must be done specifically according to the rules laid out by the IRS. Any failure to follow even a single part of the procedure will result in the loss of the benefits associated with 1031 exchanges, even if all the remaining rules are followed to the letter.

Savvy real estate investors are therefore keenly aware of the following key elements of a 1031 exchange:

1. The sale of the appreciated property, and the treatment of the proceeds

When the original property is sold, it is imperative that the investor does not take receipt of the funds generated by the sale. Instead, they are sent directly from escrow to a pre-selected independent third party, known as the qualified intermediary (QI) or the 1031 exchange facilitator. These professionals know to place the funds in an independent, FDIC-insured account, taking care not to commingle these funds with those of any other investors. The funds remain in this account until they are needed for the purchase of the replacement property.

2. The selection of the replacement property

As soon as the proceeds from the original sale are placed with an intermediary, two important clocks start ticking: the 45-day window during which a replacement property (or properties) must be identified and the 180-day window during which the second transaction must be closed. In the initial 45 days, the investor must identify at least one property or as many as the 200% rule would allow that will replace the relinquished property. Ideally, the property or properties in question will be equal to or greater in value than the relinquished property. (The investor can also choose a property of lesser value and commit additional funds to capital improvements; those funds will be counted towards the final net worth of the replacement property.)

Either way, the investor must identify the replacement property to the intermediary within 45 days of the closing of the first transaction; failure to do so invalidates the 1031 exchange. As far as replacement property ID rules there is the 3 property rule, the 95% rule, and the 200% rule which we discuss in more detail in our 1031 Exchange Masterclass taught by Daniel Goodwin.

3. Closing the deal on the replacement property

The investor has only 180 days to close the transaction for the replacement property. Accordingly, it’s usually considered best not to be overly communicative that the replacement property being sought is part of a 1031 exchange until a price is agreed upon; the owner of the replacement property would immediately understand that the investor is under a deadline, which translates into leverage for the seller and increased pressure for the buyer. Nevertheless, it is critical that not only is the price agreed to, but the entire transaction is closed within 180 days of the sale of the relinquished property. As with the sale of the relinquished property, it must be noted in the paperwork that the purchase of the replacement property is part of a 1031 exchange.

The importance of the 45- and 180-day deadlines in a 1031 exchange cannot be overstated. The IRS is inflexible, offering adjustments to these timelines only in the event of a Presidentially declared disaster or state of emergency. Failure to achieve the necessary steps within these windows, or improperly processing the 1031 exchange, potentially invalidates the entire exchange. Such an invalidation would subject the investor to significant taxes, possibly including the treatment of the transaction as ordinary income instead of capital gains; as ordinary income tax rates are significantly higher than capital gains tax rates, the resulting penalty could be severe.

However, with a carefully constructed transaction, and the efforts of a professional QI or exchange facilitator, a 1031 exchange can pay you handsome dividends, and defer capital gains taxes, for years and years to follow. Choosing a qualified intermediary is a critical step for the investor, as a capable, experienced QI will facilitate the transaction and ensure that the process is seamless for the investor.

Make a huge difference in your future investment potential

Master The 1031 Exchange Masterclass

A Timeline for A Delayed Exchange

As delayed exchanges are the most common type of a 1031 exchange, it’s imperative for investors to fully understand the importance of following the timeline prescribed by the IRS in order to secure the tax benefits of successfully completing the exchange. Follow the timelines, and capital gains taxes can be deferred indefinitely, possibly even forever. But a single misstep along these carefully constructed timelines can result in the invalidation of the entire exchange, and a whopper of a capital gains tax bill to accompany it.

Before We Begin: The Selection of a Qualified Intermediary (QI)

All 1031 exchanges are facilitated by a qualified intermediary, whose first critical function is to take possession of the proceeds of the sale of the property in question. If the investor seeking to execute a 1031 exchange takes constructive receipt of these funds, little else matters; there is no possibility to execute a 1031 exchange. Accordingly, the choice of a qualified intermediary, or exchange facilitator, is central to the process, and a good QI will ensure a smooth and seamless process for the investor.

Day 1: The relinquished property is sold

The clock starts ticking on a 1031 exchange as soon as the originally-held property, also known as the relinquished property, is sold, and the proceeds of the sale are placed with a QI.

There are two critical deadlines to adhere to in a 1031 exchange: the 45-day deadline, by which at least one, and as many as three, replacement properties must be identified; and the 180-day deadline, by which the transaction(s) must be closed. The sale of the relinquished property is day one of both of these deadlines.

Day 1-45: The Identification Period

The 45 days following the sale of the relinquished property are known as the identification period. The investor must identify potential replacement properties that will constitute the second part of the 1031 exchange.

There are some rules to keep in mind as the investor identifies the property, or properties, in question. We will limit our discussion to the three most important ones.

The 3 Property Rule

The bulk of 1031 exchanges consist of a one-for-one property swap. The investor is, however, allowed to designate as many as three properties for the exchange. Some investors choose to designate three properties so that they can retain the option of selecting one of the three; others choose to exchange their property for all three designated replacement properties. The general limitation of three properties is known as the three-property rule, and it’s important that all three properties are identified during the 45-day identification period, even if the investor ultimately chooses not to include all three in the exchange.

The 200% Rule

The IRS is agnostic as to whether an investor chooses a single replacement property, or up to three. However, the aggregate value cannot generally exceed 200% of the fair market value of the relinquished property. So an investor selling a $1.5 million investment property, for example, is held to a $3 million limit for the replacement(s). In this example, they can identify three replacement properties worth $1 million each, or a single replacement property worth $3 million, but they would run afoul of Section 1031 of the IRC if they tried to identify a pair of $2 million properties, or a single property worth $5 million. In that case, the exchange would be treated as if the investor had failed to identify any replacement properties at all, having failed to identify any which satisfied the 200% rule.

The 95% Rule

There is an exception to both of these rules, however. Investors are permitted not only to exceed three identified properties but to exceed a total of 200% of the fair market value of the relinquished property, if (and only if!) they can successfully close on 95% of the value of each of the replacement properties in question. We’ll review all three of these critical rules—generally referenced as the three-property rule, the 200% rule, and the 95% rule—in much greater detail later in this guide. We also examine all three rules in great depth in our 1031 Exchange Masterclass.

One last consideration to follow during the Identification Period is the identification process itself. One way to identify a replacement property is to close on the property itself during the identification period; any property actually acquired during this 45-day period is deemed to have satisfied the identification requirement. This method makes up a minority of 1031 exchanges, though. Most investors avail themselves of the additional time by signing an Identification Notice and delivering it to the QI no later than day 45 of the identification period. (The Notice can also be delivered to the seller of the replacement property, the title company, or the escrow agent, as long as it avoids landing in the hands of a disqualified person, such as a family member of the exchanger.)

It’s critical that a properly executed Identification Notice not only be signed by the exchanger, but also provide a clear and unambiguous description of the replacement property or properties in question. Most commonly, that description is a street address or a legal description of the property, though it can also be a clearly distinguishable and commonly known name. (So while “that huge skyscraper in Houston that’s the tallest building in Texas” would be insufficient, identifying it as “600 Travis Street, Houston, TX” or “the JP Morgan Chase Tower” is clear enough.)

Where needed, the Notice should also include the percentage of the property being acquired, as well as a description of any improvements being made on the property.

Days 46 – 180 (or 1-180): The Exchange Period

Once the replacement property has been identified, the transaction is on the clock, with an intractable buzzer sounding at the conclusion of day 180. By the end of the 180th day following the sale of the relinquished property, the transaction must be closed. Failure to close it means the loss of all the tax benefits associated with a 1031 exchange. (Section 1031 of the Code actually states that the deadline is the earlier of 180 days or the Federal tax return due date for the year in which the exchange commenced; however, since the IRS routinely grants extensions to October 15th of any given year upon request, the 180 days remains the de facto deadline.)

“By the end of the 180th day following the sale of the relinquished property, the transaction must be closed. Failure to close it means the loss of all the tax benefits associated with a 1031 exchange.”

These Are Deadlines, Not Guidelines

The IRS is famously inflexible in general, and nowhere is this lack of wiggle room clearer than the strict deadlines of 45 days for the identification period, and 180 days for the exchange period. It matters not at all if day 45 or day 180 (or both) fall on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, nor does it matter if compelling personal circumstances, including a death in the family or other calamity, beset you as the deadline approaches. Failure to identify property by the end of day 45, or to receive the replacement property by the end of day 180, invalidates a 1031 exchange.

The only exception to this rule is if the IRS issues a Disaster Relief Notice, usually in response to a Federally declared disaster, an act of terrorism, or military action. In such cases, the IRS may elect to extend deadlines by up to 120 days. Even in such cases, it’s important to note that a declaration of disaster by a President, FEMA, or other Federal agency is not sufficient; the IRS itself must issue a formal Notice on its website.

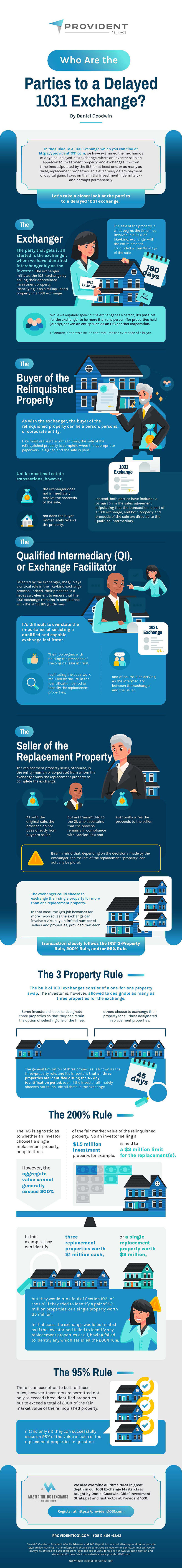

Who Are The Parties to a Delayed 1031 Exchange?

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC, OR VIEW IT BELOW.

We have examined the mechanics of a typical delayed 1031 exchange, where an investor sells an appreciated investment property, and exchanges it within timelines stipulated by the IRS for at least one, or as many as three, replacement properties. This effectively defers payment of capital gains taxes on the initial investment indefinitely… and perhaps permanently.

Let’s take a closer look at the parties to a delayed 1031 exchange.

The Exchanger

The party that gets it all started is the exchanger, whom we have identified interchangeably as the investor in this guide. The exchanger initiates the 1031 exchange by selling their appreciated investment property, identifying it as a relinquished property in a 1031 exchange. The sale of the property is what begins the timelines involved in a 1031, or like-kind, exchange, with the entire process concluded within 180 days of the sale.

While we regularly speak of the exchanger as a person, it’s possible for the exchanger to be more than one person (for properties held jointly), or even an entity such as an LLC or other corporation.

Of course, if there’s a seller, that requires the existence of a buyer.

The Buyer Of the Relinquished Property

As with the exchanger, the buyer of the relinquished property can be a person, persons, or corporate entity. Like most real estate transactions, the sale of the relinquished property is complete when the appropriate paperwork is signed and the sale is paid. Unlike most real estate transactions, however, the exchanger does not immediately receive the proceeds of the sale, nor does the buyer immediately receive the property. Instead, both parties have included a paragraph in the sales agreement stipulating that the transaction is part of a 1031 exchange, and both property and proceeds of the sale are directed to the Qualified Intermediary.

The Qualified Intermediary (QI), or Exchange Facilitator

Selected by the exchanger, the QI plays a critical role in the like-kind exchange process; indeed, their presence is a necessary element to ensure that the 1031 exchange remains in compliance with the strict IRS guidelines. It’s difficult to overstate the importance of selecting a qualified and capable exchange facilitator. Their job begins with holding the proceeds of the original sale in trust, facilitating the paperwork required by the IRS in the identification period to identify the replacement properties, and of course also serving as the intermediary between the exchanger and the Seller.

The Seller of the Replacement Property

The replacement property seller, of course, is the entity (human or corporate) from whom the exchanger buys the replacement property to complete the exchange. As with the original sale, the proceeds do not pass directly from buyer to seller, but are transmitted to the QI, who ascertains that the process remains in compliance with Section 1031 and eventually wires the proceeds to the seller.

Bear in mind that, depending on the decisions made by the exchanger, the “seller” of the replacement “property” can actually be plural. The exchanger could choose to exchange their single property for more than one replacement property. In that case, the QI’s job becomes far more involved, as the exchange can involve a virtually unlimited number of sellers and properties, provided that each transaction closely follows the IRS’ three-property rule, 200% rule, and/or 95% rule. We’ll cover those three rules in much greater detail later in this guide, and of course we examine them extensively in the 1031 Exchange Masterclass.

Infographic

Who Are the Parties to a Delayed 1031 Exchange

Click here to download the Infographic: Who Are The Parties to a Delayed 1031 Exchange?

Understanding Reverse 1031 Exchanges

As we covered in some detail in Chapter 2 of this guide, 1031 exchanges are more than a century old, but they have evolved considerably over the years. Initially, all exchanges were confined to a single business day, during which two transactions (the sale of the relinquished property and the purchase of the replacement property) had to be closed simultaneously.

Like-Kind and Timelines

Following the Supreme Court’s 1979 Starker decision, however, the IRS acknowledged that the sale of one property and the purchase of a subsequent replacement property had to be like-kind, but not same-day, and they set about establishing timelines for which such delayed exchanges could take place and remain eligible for preferential tax treatment. Soon thereafter (in 1984), 45- and 180-day limits were imposed, requiring a replacement property to be identified and purchased, respectively, within those time frames.

Left unaddressed, however, was the question about the order of these events. Many assumed that it didn’t matter whether the sale of the relinquished property preceded the purchase of the replacement property, as long as both events were concluded within the timelines proscribed by the IRS. But while the IRS never challenged the legitimacy of the reverse exchange, in which the purchase of the replacement property precedes the sale of the property being replaced, they also neglected to confirm the validity of this procedure for nearly two decades, even while permitting them to take place over that time.

Formal recognition of the reverse exchange

Finally, the IRS issued Revenue Procedure 2000-37 to formally recognize the reverse exchange, or “parking” exchange, structure. And while the terminology involved in a reverse exchange is different from the delayed exchange, the two processes parallel each other closely.

Exchange Accommodation Titleholder, or EAT

As with any 1031 exchange, a reverse exchange requires the expertise of a third party so that the taxpayer avoids being in possession of both the relinquished and the replacement property at the same time. This third party, the Exchange Accommodation Titleholder (or EAT), plays a similar role to the qualified intermediary in a delayed exchange.

Qualified Exchange Accommodation Agreement, or QEAA

The structure of the parking exchange is spelled out in a qualified exchange accommodation agreement, or QEAA. The IRS safe harbor guidelines require both the existence of the QEAA, and the intermediary role played by the EAT.

A typical reverse exchange

A typical reverse exchange will proceed something like this:

- The taxpayer finds an investment property they wish to buy. Typically, the purchase is completed, and the title is transferred not to the taxpayer, but to the Exchange Accommodation Titleholder (the EAT), since the taxpayer cannot own both the relinquished and replacement properties at the same time.

- Within five business days of the transfer to the EAT, there must be a written and executed Qualified Exchange Accommodation Agreement (QEAA). The QEAA explicitly states the taxpayer’s intention that the property held by the EAT is part of a 1031 exchange.

- Within 45 days of the “parking” of the replacement property to the EAT, the relinquished property or properties (up to three) must be identified, in writing.

- Within 180 days of the transfer, both transactions must be completed. The EAT concludes the exchange by deeding the relinquished property to the buyer, and transferring the replacement property title to the exchanger.

Requirements

The parallels between the requirements involved in a delayed exchange and reverse exchange are obvious, and the same rules that apply to the replacement properties in a delayed exchange—the three-property rule, the 200% rule, and the 95% rule—all apply to the relinquished property or properties in a reverse exchange.

The language in Revenue Procedure 2000-37 acknowledges that most reverse exchanges involve the taxpayer parking the replacement property with an EAT while identifying the relinquished property and arranging for its sale. This is also known as the “exchange last” method. Depending on the circumstances, however, taxpayers may find it advantageous to use an “exchange first” method, parking the relinquished property with the EAT until the taxpayer is ready to complete the exchange (with a hard limit of 180 days, of course).

Factors

Any number of factors will determine which approach is best for the taxpayer, including the funding being used to acquire the replacement property (since the relinquished property has yet to be sold), the existing equity in the relinquished property, the presence of liens on the relinquished property, or the taxpayer’s intention to make improvements on the replacement property.

Since IRS regulations prohibit the use of exchange funds to make improvements on a property they already own, for example, a taxpayer seeking to make improvements on a replacement property would have to park the replacement property. They could then enter into an Improvement, or Build to Suit, exchange, and while the replacement property is parked with the EAT, improvements can be completed within the 180-day period. This would enable the EAT to ultimately complete the exchange by transferring the replacement property back to the taxpayer at the higher improved value.

Increased flexibility

Reverse exchanges are inherently more complex than their more straightforward delayed exchange counterpart, and they carry no increased tax benefits beyond any other form of 1031 exchange. More than anything, they offer increased flexibility for taxpayers whose individual circumstances dictate their need for them.

Working with a highly qualified advisor is a must here, and taxpayers seeking a more in-depth look at 1031 exchanges of all kinds would benefit tremendously from our 1031 Exchange Masterclass.

The 1031 Exchange Timeline

Share this Infographic Image on Your Site

<p><strong>Please include attribution to https://provident1031.com/ with this graphic.</strong><br /><br /><a href=’https://provident1031.com/blog/2022/04/16/1031-exchange-timeline/’><img src=’https://provident1031.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/P1031_1021_exchange_timeline.jpg’ alt=’1031 Exchange Transaction and Timeline’ width=’1200px’ /></a></p>

The Role of the Qualified Intermediary

The entities involved in a 1031 exchange are quite similar to those involved in any other real estate transaction that encompasses two separate investment properties. Both properties require a buyer and a seller, with the exchanger playing a dual role, as the seller of one (the relinquished property) and the buyer of the other (the replacement property). And of course, both buyer and seller have the usual cadre of professionals to assist with the transaction: Realtors, inspectors, closing agents, attorneys, accountants, and anyone else they might think useful.

There is, however, one professional that’s not needed in a conventional real estate transaction, but absolutely central to a 1031 exchange. In fact, the exchange literally cannot take place without the services of a Qualified Intermediary, or QI. Also sometimes referenced as an exchange facilitator, the QI is integral to a successful 1031 exchange.

So let’s break it down.

What is it that a good QI brings to the process?

For starters, the “Q” in “QI” stands for qualified. So it’s important to know who’s not qualified to serve as an intermediary in this transaction:

-

The exchanger. If you’re the entity that is exchanging investment properties in a like-kind exchange, you are immediately ruled out as the QI, which will be obvious as we study the role of a QI.

-

Anyone with a prior professional relationship with the exchanger. If you’ve served as the exchanger’s accountant, attorney, employee, or investment banker at any time, or as the exchanger’s real estate agent or broker in the two years preceding the transfer of the relinquished property by the exchanger, then Section 1031 will treat you as the exchanger’s agent, and you are disqualified as an intermediary.

-

Anyone related to the exchanger, or to the exchanger’s agents as defined above. The IRS would frown upon the services of your accountant’s spouse or sibling as a QI, just as much as it would disapprove of the accountant themselves.

The simplest way to put it is that a qualified intermediary must be a third party, independent of the exchanger. The QI can be a person, company, or other entity, but the independent nature of the role is to ensure that the transaction remains in compliance with the constructive receipt doctrine spelled out by the IRS in Section 1031. The exchanger cannot receive the proceeds of the sale, nor any benefits associated with the replacement property, until the exchange is complete.

Somewhat surprisingly, there are no current Federal regulations governing the exchange industry as a whole; virtually anyone who does not run afoul of the above disqualifiers can become a qualified intermediary. That places the burden of responsibility directly on the exchanger’s shoulders, as the QI plays such a critical role in the exchange that its importance cannot be overstated. Doing due diligence on the prospective QI is therefore crucial. The exchanger should ascertain, at a bare minimum, the following facts about the QI under consideration:

- prior experience in 1031 exchanges (nobody wants to serve as a learning experience!)

- the methods by which the QI will be handling the funds of all transactions

- the fee structure of the QI

Let’s break these down one at a time.

Prior experience

A qualified intermediary will be counted on to not only provide guidance and advice regarding timelines and procedures but will also have to carry out various aspects of these procedures, without which the exchange may lose some or all of its considerable tax advantages. As such, the exchanger should look for evidence that the QI has been there and done this before, so that everyone can rest assured that the myriad of details necessary to a successful 1031 exchange are seen to.

Multiple forms of documentation are required on the part of the QI, including (but not limited to): the exchange agreement, the assignment agreements for both purchase and sale, notices of assignment to the buyer and the seller, replacement property identification notice(s), exchange account forms, qualified escrow agreements, and final instructions to the closing officers. Exchangers should be satisfied that their QI is comfortable and capable of handling each part of the transactions.

Handling of funds

Since the exchanger is prohibited from taking constructive (or actual) receipt of the proceeds of the 1031 exchange until the exchange itself is complete, it’s imperative that the QI set up a separate bank account for the benefit of the exchanger, until the funds are needed to purchase the replacement property. These escrow accounts should carry the maximum levels of FDIC insurance, and the QI should also ascertain that the account’s escrow agreement carries a dual signature requirement—one from the exchanger, one from the QI—in order to effectuate any disbursements.

It’s important for the QI to know that, in addition to the prohibition against constructive receipt of the funds, the exchanger is also prevented from obtaining any ancillary benefits from the funds, including pledging them as collateral or borrowing against them. Failure to comply with these requirements will result in the proceeds being taxable as boot, a subject we discuss at length in our 1031 Master Class and will cover in great detail later in this guide. Suffice it to say for the moment that having the proceeds taxable as boot negates the tax advantages of a 1031 exchange and is to be avoided at all costs.

Fees

As with all professional services, no one performs the intricate work of a QI for free, and if someone volunteers to do so, then caveat emptor! Having said that, fees charged by qualified intermediaries vary widely, depending on several factors. Generally speaking, the fees are presented as either a flat fee or as a percentage of the selling price.

In addition, the exchange agreement should specify how interest is handled, since the proceeds of the sale will remain in escrow up to 180 days. This is less of an issue when interest rates hover around zero, but more so in a rising interest rate environment. Interest can ultimately be assigned to the exchanger, to the QI, or divided between the two.

All told, the exchanger can reasonably expect to pay anywhere from $1,000 to $1,500 or more (exclusive of the treatment of interest) for the services of a good qualified intermediary, and could even move beyond that range if the exchange in question includes more than one relinquished or replacement property.

As this fee is contemplated, it’s important to remember that you’re counting on the QI to:

- acquire the relinquished property from the exchanger

- transfer the relinquished property to the buyer

- acquire the replacement property from the seller

- transfer the replacement property to the exchanger

- hold and protect proceeds from these transactions, in compliance with Sec. 1031

- prepare the necessary documentation for each transaction, from beginning to end

- provide guidance and advice, including strict adherence to time limits

- serve as primary troubleshooter and problem solver for any issues that arise

In sum, a good QI’s fees are well-earned, and a tiny percentage of the significant tax advantages to be found in a successful 1031 exchange.

Infographic

The Role of the Qualified Intermediary

Looking For A Reputable Qualified Intermediary?

"*" indicates required fields

What is Boot?

Avoid Boot in a 1031 Exchange

Kenny Anderson was looking to diversify his investments.

A veteran real estate investor, Kenny had just finished paying the mortgage on a $2.5 million office property; it boasted 86% occupancy in a market where the average was closer to 65%, so he knew he had a great property on his hands. But the state of the commercial real estate market was giving him pause, and he was no longer comfortable with this single asset as his primary real estate holding.

So Kenny used an experienced qualified intermediary (QI) to facilitate a 1031 exchange that sold his office property for $3.5 million, but also enabled his purchase of three other investment properties: an apartment building ($1.5 million), two locations in a local condo development ($750,000 each), and a smaller commercial office space in a strip mall ($1 million).

The QI did a great job in service to his client. He made sure that Kenny identified all four replacement properties in writing within 45 days of the original sale of his office building. He closed the purchase of all four replacement properties within 180 days of that sale. And most importantly, by making sure that Kenny reinvested all of the proceeds of his sale into the replacement properties, he made sure that there was no boot in the sale, thereby enabling Kenny to defer paying taxes on the entire transaction.

Boot?

1031 exchanges enable the taxpayer to defer capital gains taxes on the sale of an investment property, provided that the transaction meets all the requirements, one of which is to reinvest 100% of the proceeds of the sale into another investment property. Forgoing the reinvestment and keeping the proceeds of the sale, on the other hand, would render all the capital gains from the sale taxable. In the example above, Kenny had originally paid $2.5 million for his office building, and sold it for $3.5 million, meaning he faced a tax bill on the $1 million capital gain, With long-term capital gains tax rates of 20%, Kenny would have owed $200,000 (plus whatever state capital gains taxes he would have incurred).

The 1031 exchange permitted him to defer the payment of those taxes, but only because he reinvested all the proceeds of the sale. If Kenny had sold his building for $3.5 million and exchanged into a replacement property valued at only $3.4 million, the $100,000 difference would have been “boot,” or the amount of the sale that was not exchanged into a like-kind property. Importantly, boot is taxed not as a capital gain, but as ordinary income. If Kenny were in the highest Federal tax bracket of 37%, this would cost him $37,000, undercutting the tax benefits of the 1031 exchange structure.

Cash boot

The scenario above would involve what’s known as cash boot. Any difference between the value of the relinquished property and a lower-priced replacement property (or properties) is cash boot, taxable as ordinary income. Note that Kenny’s 1-for-4 swap detailed above entailed four properties that were each valued below the proceeds of the $3.5 million relinquished property sale: one at $1.5 million, two at $750,000 each, and one at $1 million. But the aggregate value of the four properties, $4 million, exceeds the original $3.5 million sale price, and since Kenny met the timelines with all four transactions, the 1031 exchange enabled him to successfully defer the payment of capital gains taxes, and avoid the onerous payment of taxes on boot.

Most 1031 exchanges involve 1-for-1 like-kind swaps, and as such, the most important thing the investor can do to avoid cash boot (in addition to reinvesting 100% of the proceeds into the replacement property) is to make sure that the value of the replacement property meets or exceeds the value of the relinquished property.

Mortgage boot

Kenny’s 1031 exchange involved a relinquished property whose mortgage had just been paid, and four replacement properties that were also free and clear. But what if there had been mortgages involved on either or both sides of the transaction?

The most important thing is that the outstanding mortgage on the relinquished property does not exceed the outstanding mortgage of the replacement property. Let’s simplify Kenny’s transaction to illustrate. Assume that he still owes $200,000 on his $3.5 million property, and his exchange involves a single, $4 million replacement property. If the replacement property also carries a $200,000 mortgage, the dollar-for-dollar match means there is no mortgage boot. If, however, the replacement property has no mortgage, the $200,000 difference would qualify as mortgage boot, once again taxable as ordinary income.

Mortgage boot is simple enough to avoid, either by paying down the mortgage on the relinquished property prior to sale, or by taking a $200,000 mortgage on the replacement property as part of the purchase agreement.

Double jeopardy?

It’s entirely possible to have both cash boot and mortgage boot in the same transaction.

Let’s look at a $1 million relinquished property with a $100,000 mortgage that’s paired with a $950,000 replacement property with a remaining $20,000 mortgage. The unfortunate taxpayer has incurred cash boot of $50,000, and mortgage boot of $80,000.

If there’s a silver lining to this particular quagmire, it’s that the IRS will not tax both forms of boot; they will, of course, tax the larger number, but in this case, the taxpayer is off the hook for the smaller cash boot.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of a knowledgeable and experienced qualified intermediary, who can most likely structure a 1031 exchange that will minimize the chances of facing such a situation.

Personal property boot

While it’s relatively rare, it does happen from time to time that some of the property in a like-kind exchange falls outside the definition of “like kind,” usually because it represents an asset that will not be used as an investment or in a business.

Let’s look at an exchange where an investor is selling a $1.3 million building for a $1 million replacement property. Knowing of the investor’s taste for luxury cars, the replacement property’s seller offers to bridge the gap by including a Lamborghini with a fair market value of $300,000. The taxpayer may well enjoy the ride, but not the tax situation he’s left in; the Lambo would likely be deemed a personal asset, not an investment property, and the resulting $300,000 personal property boot would be taxable as ordinary income.

While this is a fairly obvious example, investors should study contract terms to make sure there’s no crossover between investment property and personal property in a 1031 exchange.

Avoiding boot

With its higher tax rate undercutting the presumed tax benefits of a 1031 exchange, investors would do well to avoid the unpleasant surprise of boot as part of their transaction. A good qualified intermediary is a considerable asset in ensuring that 1031 exchanges maximize their financial benefits.

It’s critical that investors follow these guidelines:

- Make sure the replacement property is as valuable, or more so, than the relinquished property.

- Reinvest 100% of the proceeds of the sale into the replacement property.

- Make sure the replacement property has a mortgage equal to or greater than the one on the relinquished property.

- Analyze the replacement property’s contract to ensure that there is no commingling of investment property and personal property.

Mitigating strategies

Despite everyone’s best efforts, an investor may still find themselves with boot on their hands. Debt replacement strategies can certainly address mortgage boot. Investing boot in a DST (Delaware Statutory Trust) provides an effective tax shelter, as well as further diversification into high-quality real estate assets.

Investors might also consider reinvesting the net equity into the replacement property by using a construction 1031 exchange (also known as an improvement exchange or a build-to-suit exchange), as discussed elsewhere in this guide.

Be sure to consider all your options before succumbing to the trap of paying taxes on boot.

Demystifying the 1031 Exchange 200 Rule

The IRS doesn’t offer significant tax savings strategies on a regular basis. And when they do, you can safely bet that there will be many I’s to dot and many T’s to cross.

Real estate investors know this all too well: most knowledgeable investors have some experience with 1031 exchanges, also known as like-kind exchanges, because of the tantalizing tax breaks they offer. With a well-constructed 1031 exchange, an investor can sell an appreciated piece of investment property, replace it with one of equal or greater value, and defer the payment of capital gains taxes on the relinquished property.

Of course, to capitalize on this extraordinary opportunity, it’s critical to follow the procedure outlined in Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code to the letter. And especially for those investors looking to upsize their investment property, the 1031 exchange 200 rule becomes a critical part of their planning.

Let’s review

when entering into a 1031 exchange, there’s a multi-step process that must be followed. When the first property is sold, it has to be identified as the “relinquished property” in a like-kind exchange. That starts the clock ticking on the 45-day period that the investor has to identify as many as three “replacement properties” that they will be purchasing, using the proceeds of the sale to achieve their goal.

Enter the 1031 exchange 200 rule, also referred to as the 200% rule. The value of the replacement property (or properties, if more than one is ultimately purchased) cannot exceed 200% of the value of the relinquished property. Go over that limit, and the ability to defer the capital gain tax on the original sale is threatened.

Example: Meet Martin Barrett

Let’s use the example of Martin Barrett, who wants to move away from the commercial real estate space and into residential, while also increasing his real estate footprint. He’s selling his New Jersey office building for $800,000, and with the help of his qualified intermediary, he has located three potential replacement properties:

- A multi-family house worth $600,000;

- A small apartment building with a $975,000 price tag; and

- A larger apartment building selling for $1.5 million.

The math here is simple and straightforward: $800,000 x 2 = $1.6 million, which represents 200% of the value of the relinquished property. Marty wants to stay under that number to make sure none of the tax benefits of his 1031 exchange are threatened.

Marty loves the multi-family house, with its small number of paying tenants and its excellent condition. But if he chooses that, then the $200,000 difference between the two properties, known as boot, is taxable to him as ordinary income, and would largely defeat the purpose of the exchange. So he’s safe according to the 200 rule, but he’s faced with a tax bill on the $200,000 difference. As a high earner in New Jersey, a high-tax state, the combination of the Federal and state liabilities would exceed $50,000.

Of course, if Marty really loves the house that much, he could close on both the house and the smaller of the two apartment buildings. The combined value of $1.575 million is just under the $1.6 million limit, so in theory, he’s safely under the 200% limit. But such a deal presents him with two caveats.

First, he has to be quite certain about the property valuations. Coming so close to the limit means that if he is faced with any kind of a bidding war, the entire transaction could be jeopardized. With only $25,000 below the 200% limit, there isn’t a lot of wiggle room in a real estate market as fluid as this one, and any other interested buyers on either of the two properties could doom the deal for him.

Second, and somewhat related, Marty has 180 days to close both transactions in order to successfully complete the 1031 exchange. If he can’t close in that timeline, the parameters of the exchange shift. That’s not an insurmountable problem if he closes on the larger of the two properties, which is still an increase in value over his relinquished property, but it’s a potential fiasco if he’s left with only the multi-family house and the $50,000+ tax bill that accompanies it.

Faced with the time constraints and the moving parts, Marty goes with the third option, which provides a $100,000 margin of error between his $1.5 million purchase price and the $1.6 million limit, and also provides a less complicated exchange by limiting it to a single replacement property.

Understanding the potential advantages of the 200 rule is just one of the multiple facets of a like-kind exchange that we cover in this comprehensive Guide to 1031 Exchanges. For an even more in-depth look at like-kind exchanges, enroll in our 1031 Exchange Masterclass, an investment of time that will pay for itself many times over.

Since every 1031 exchange has unique twists and turns, it’s critical to work with a financial team you trust, including a qualified intermediary with experience and knowledge of 1031 exchanges.

Can A 1031 Exchange Be Used for New Construction?

Dr. Helen Santos had a problem that most successful businesspeople would envy: her highly successful business was growing too fast for their aging building to keep up.

She and her husband, Matthew [not their real names], are doctors with a successful practice in a small town in California. They met when they were both in medical school at Stanford, and their personal lives merged just as their professional lives did. When they began their practice together, Helen used a gift from her parents to put a down payment on an 8,000-square-foot space for their new practice. The $3 million price tag was a huge leap of faith at the time, especially with both of them still carrying student loans from med school. Twenty years later, the success of the practice and the white-hot real estate market had combined to provide them with a building that was worth $11 million, was fully paid for… and that no longer suited the needs of their growing practice.

Between a lack of parking, a need to upgrade major equipment, and general maintenance needs that would require a substantial investment to address, Helen and Matt had outgrown their practice space. Renovating the existing space was not a realistic option, given the constraints of space. They knew they had to find someplace newer and at least a little bigger to accommodate their goals, but they also knew that selling the existing building would mean an $8 million capital gain and a tax liability that they didn’t want to face.

Fortunately, they were aware of the power of 1031 exchanges for business real estate and knew that at the very least, they could defer the capital gains tax on their existing building by working with a qualified intermediary to find their new office. After scouring the market, Helen and her team managed to identify three possible replacement properties:

- a beautiful building less than ten years old, just a couple of miles from their existing practice and ready to move in with little to no renovation, for $11 million;

- an older medical building in an enviable part of town, priced at only $9.5 million but needing another $2.5 million in work to repair an aging roof, expand inadequate parking, and further modernize the facility inside and out;

- and a tiny abandoned building on an outsized plot of land that would have to be razed in favor of new construction. The relatively paltry sum of $1.5 million to acquire the land would be accompanied by demolition and construction costs that her team estimated at just over $12 million.

Helen and Matt and their team prepared to identify all three properties within the 45-day limit proscribed by Section 1031 of the Code, but had misgivings about the last two properties and put the question to their intermediary directly:

Can I Use a 1031 Exchange for New Construction (or for Renovation)?

Helen knew that, no matter which choice was made, they had 180 calendar days from the time they sold their current office to close the transaction and acquire the replacement property. She and Matt were happily positioned to be able to take a break from the practice for as long as a year to get the new building in shape, but they knew that the IRS was not flexible on the 180-day limit. So they addressed the pros and cons of each of the properties with their team.

Property #1

The first property was as close to a “turnkey” arrangement as they could have hoped for. Everything was already in place, and move-in ready, and if they chose, they could sell their existing office and move into the new one, and have their practice up and running within a week or two. The asking price of $11 million was something they ordinarily might have haggled, but since they were selling their own office at $11 million, they knew that to avoid any capital gains tax liability, the replacement property had to be for the same price or more. The readiness of the building, and the speed with which the transaction could proceed, were tempting.

There were various aspects of the first property that they didn’t love but knew they could live with, and the other two possibilities both offered the ability to adjust the building to more exact specifications.

Property #2

The second possibility required only a handful of renovations, and everyone’s best estimate was that the entire project could easily be completed within 2-3 months, well within the 180-day limit of the exchange. The second building addressed all of their needs and most of their wants.

Property #3

Nevertheless, they found themselves pulled toward the third property, a “blank slate” that would enable them to do everything they wanted, with few limitations. But they needed reassurance that a 1031 exchange would allow for new construction, and they had serious concerns about the 180-day timeline that the law imposed.

Fortunately, construction exchanges (as they are known) are indeed permissible according to the Code. The intermediary explained that the proceeds from the sale of the relinquished property could be used for the costs of construction, much as they could be used for renovation costs, although it was essential that neither she nor Matt took receipt of the funds; instead, an escrow account controlled by the intermediary would have to be established to pay for all expenses.

Helen and Matt continued to have doubts about the feasibility of the new building being substantially completed within the timeline that the statute required, and didn’t want to risk making the exchange taxable by missing this critical deadline.

But armed with the knowledge that Helen and Matt had the financial flexibility to do so, the intermediary suggested a reverse construction exchange to enable the deal to take place. By taking on the purchase of the replacement property before selling their own building, the work on the new building could begin on day one, and the doctors could maintain their current practice while their ambitious construction process proceeded.

The 180-day limit was still applicable, and Helen and Matt still needed to complete both sides of the transaction within that time, but the extra time afforded by the purchase of the replacement property in advance of the sale of the relinquished property just might make the needed difference.

Satisfied that the work would indeed be substantially done by the 180-day deadline, Helen and Matt elected to proceed with the new construction option.

In structuring a 1031 exchange that purchased a $1.5 million plot of land, and subsequently erected a $12 million building, the doctors were able to sell their property for their $11 million asking price, indefinitely deferring the payment of tax on the capital gain of $8 million (which their accountant estimated saved them, as high earners in a high tax state, a $1.6 million Federal capital gains tax, as well as the California capital gains tax of 13.3%, or $1.064 million).

Of course, Helen and Matt understood that the tax of $2,664,000 was not eliminated, merely deferred. But instead of paying it to Uncle Sam, they were pleased that they could deploy it as the difference between their $11 million selling price and the $13.5 million needed to secure the new building. Had they not needed to use the money for construction, they could have simply invested it and enjoyed the income it generated, even as the principle remained available for the eventual payment of the taxes. Either way, the ability to retain these funds instead of paying them as taxes represents the primary advantage of the 1031 exchange.

The Santos transaction was complicated, and fraught with potential obstacles, but the difference makers in the deal were the trusted financial advisors that Helen and Matt hired to represent them every step of the way. If you take nothing else from the Santos story, remember these important lessons:

- 1031 exchanges can be used for existing properties as well as for new construction.

- While most 1031 exchanges involve selling one property and subsequently buying a second, the order of the transactions is not carved in stone, provided all the relevant timelines are observed.

- The importance of an experienced, highly qualified team to guide you through the intricacies of a 1031 exchange cannot be overstated.

Can I Use a 1031 Exchange to Acquire International Real Estate?

If you’re a savvy real estate investor looking to expand your portfolio beyond the borders of the United States, you may wonder if you can use a 1031 exchange to acquire international real estate. The short answer is yes, but it has some important caveats and considerations.

1031 exchange basics

First, let’s review the basics of a 1031 exchange. This tax-deferred transaction allows investors to sell an investment property and reinvest the proceeds into a “like-kind” property, deferring capital gains taxes in the process. The key phrase here is “like kind,” which means that the properties involved in the exchange must be similar in nature or character, even if they differ in grade or quality.

Can international real estate be considered “like-kind”?

So, can international real estate be considered “like-kind” to U.S. real estate for the purposes of a 1031 exchange? Unfortunately, the answer is no. The IRS clearly states (in Section 1031(h) of the Code) that “real property located in the United States and real property located outside the United States are not property of a like-kind.”

But . . .

However, this doesn’t mean that international real estate is completely off-limits for 1031 exchanges. In fact, international real estate can be exchanged for other international real estate, as long as the properties are considered like-kind. For example, let’s say an investor owns a rental property in Costa Rica and wants to exchange it for a similar property in Panama. As long as both properties are held for investment purposes and are considered similar in nature or character, this could potentially qualify as a valid 1031 exchange.

More complex and challenging

Bear in mind that exchanging international real estate can be more complex and challenging than exchanging domestic properties. Investors must navigate a host of additional legal, tax, and logistical considerations, such as foreign ownership restrictions, currency exchange risks, and differences in property rights and land registration systems.

Real estate located in U.S. territories outside the 50 states, such as Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam, occupy a special niche within the IRS, particularly when it comes to 1031 exchanges.

Three “Coordinated Territories” of the United States

While Section 7701(a)(9) of the Code limits the definition of the “United States” to “only the States and the District of Columbia,” Section 932 of the Code carves out an exception for the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Section 935 of the Code includes the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam. These three “Coordinated Territories” of the U.S. are incorporated into Section 1031, such that real properties in any of the three qualify as like-kind to any other U.S. property.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico, notably, is considered a Protectorate of the U.S. but not a “coordinated territory.” Accordingly, real estate in Puerto Rico is not considered like-kind to U.S. real estate for the purposes of a 1031 exchange. Despite several explicit legislative attempts to remedy the situation, most recently in 2021, none of the bills proposed have managed to become law. So unfortunately, for U.S. real estate investors seeking to expand their portfolios with island vacation property, real estate in Puerto Rico remains ineligible for consideration under Section 1031, unless the relinquished property is also a non-U.S. property.

Investors who are seeking to expand their holdings into Puerto Rico might consider a Qualified Opportunity Fund with holdings in Puerto Rico. Currently Puerto Rico has over 850 Qualified Opportunity Zones, including more than twenty in non-low-income tracts that are contiguous to low-income zones. While there would be much that is attractive about such an investment, it’s important to note that irrespective of geography, QOZ funds are not “real property,” and are thus ineligible to serve as replacement properties in a 1031 exchange.

Work with experienced tax and legal professionals when considering a 1031 exchange

As with its domestic counterparts, it is essential for investors to work with experienced tax and legal professionals when considering a 1031 exchange involving international real estate. The rules and regulations surrounding these transactions can be complex and vary widely depending on the specific countries and properties involved. In addition to the legal and tax considerations, investors must also be prepared for the practical challenges of owning and managing international real estate. Language barriers, cultural differences, and distance can all make it more difficult to oversee an international property investment effectively.

International real estate can offer compelling opportunities

Despite these challenges, international real estate can offer compelling opportunities for diversification, growth, and potentially higher yields. For investors who are prepared to navigate the complexities and risks, a 1031 exchange can be a powerful tool for building a global real estate portfolio while deferring capital gains taxes.

A 1031 exchange can be a valuable tool for savvy investors

In short, while international real estate is not considered like-kind to U.S. real estate for the purposes of a 1031 exchange, investors can still potentially use this tax-deferral strategy to swap one international property for another. With the right approach and due diligence, a 1031 exchange can be a valuable tool for savvy investors looking to expand their horizons and build wealth through international real estate.

Can A Trust Do A 1031 Exchange?

1031 Exchanges: A powerful tool for real estate investors looking to defer capital gains taxes and grow their wealth

1031 exchanges have long been a powerful tool for real estate investors looking to defer capital gains taxes and grow their wealth. By allowing investors to sell an investment property and reinvest the proceeds into a similar property, 1031 exchanges provide a way to keep money working in the real estate market without incurring an immediate tax liability.

This tax-deferral strategy has helped countless investors expand their portfolios, diversify their holdings, and build long-term wealth. However, as with any complex financial transaction, there are rules and requirements that must be followed to ensure a successful exchange.

Can a trust do a 1031 exchange?

One common question that arises is whether trusts can participate in 1031 exchanges, and if so, what special considerations must be considered.

The Internal Revenue Service’s 2008 Fact Sheet on the topic provides a simple response: “any… taxpaying entity [including trusts] may set up an exchange of business or investment properties for business or investment properties under Section 1031” of the Internal Revenue Code.

The devil is in the details

Of course, as with all good news from the IRS, the devil is in the details. When it comes to trusts and 1031 exchanges, the good news is that most types of trusts are eligible to participate, provided they meet certain criteria and follow specific rules.

Trusts that have taken advantage of Section 1031

Let’s take a look at the kinds of trusts that have historically taken advantage of Section 1031, as well as one trust that’s ineligible to do so.

The three key parties involved in a trust

With all trusts, there are three key parties involved: the grantor (the holder of the assets in question, and the party who establishes the trust), the trustee (who is legally responsible for managing the trust), and the beneficiary (or beneficiaries) of the trust, who receive the benefits of the trust. Some kinds of trusts enable a taxpayer to serve all three roles, while others are more limiting.

Revocable Living Trust

The most common type of trust used in 1031 exchanges is the revocable living trust. This type of trust is created during the grantor’s lifetime and can be modified or revoked at any time. The grantor maintains control over the trust assets and can also serve as the trustee if they choose. Because they retain control over the property and assets in the trust, as well as the ability to change the terms and conditions of the trust, the grantor is responsible for the payment of any income or capital gains taxes related to the trust since the trust does not file a separate tax return.

In the context of a 1031 exchange, a revocable living trust can sell an investment property and use the proceeds to purchase a like-kind replacement property, deferring capital gains taxes in the process.

Because grantors retain control over the assets, they may also choose to sell a relinquished property held by the trust and subsequently purchase the replacement property as an individual or vice versa. As long as all other conditions of a 1031 exchange are met, this kind of transaction is permissible in a revocable living trust.

Irrevocable Trust

Another type of trust that can participate in 1031 exchanges is an irrevocable trust. Unlike a revocable trust, an irrevocable trust cannot be easily modified or revoked once it is established.

The grantor relinquishes control over the trust assets permanently, and the trust becomes a separate legal entity. The trust bears its own tax identification number, similar to an individual’s social security number, and it is responsible for reporting all earnings and tax liabilities on an annual basis.

Grantors can technically serve as the trustees of their own irrevocable trusts, but most experts strongly advise against it. If a grantor has discretion over the distribution of trust assets, it could lead to inclusion of the trust’s assets in the grantor’s estate, which would defeat the purposes of establishing a trust in the first place.

Irrevocable trusts can be used in 1031 exchanges, but it is essential to ensure that the trust document allows for such transactions and that the trust meets all the necessary requirements.

Charitable Remainder Trusts

A subset of irrevocable trusts, charitable remainder trusts (CRTs) can also take part in 1031 exchanges, though there are some limitations that don’t necessarily apply to the revocable or irrevocable living trusts.

A CRT provides income to the grantor or other beneficiaries for a specified period, with the remainder going to a designated charity.

CRTs can sell an investment property and use the proceeds to purchase a replacement property as part of a 1031 exchange. However, the replacement property must be held in the trust, and the income generated from the property must be distributed according to the trust’s terms.

Delaware statutory trusts

Delaware statutory trusts (DSTs) also merit mention here. DSTs are established, usually by professional real estate companies to facilitate ownership of property by multiple owners, and are usually investment-grade real estate.

Once established, DSTs hold legal title to one or more properties, and investors can purchase beneficial interests in the trust. The limited powers of the trustee in a DST mean that the owners of the beneficial interests are deemed fractional owners of the properties within the trust for tax purposes, and DSTs are therefore considered valid replacement properties for 1031 exchanges.

Charitable lead trusts